PCOS and Epigenetics: It Didn’t Start With You

If you have PCOS, you might have wondered why. Was it something you did? Something your mom did? Something you could have prevented? The answer is no. PCOS is deeply rooted in genetics and epigenetics, and the factors that contribute to it may have been set in motion long before you were even born.

The Role of Epigenetics in PCOS

Epigenetics is essentially how your genes get “turned on” or “off” by things like environment, diet, and hormones. It doesn’t change your DNA, but it does change how your body reads it. That’s why two people with the exact same genes (like identical twins) can have totally different health outcomes.

When it comes to PCOS, epigenetics is a big deal. One of the biggest triggers? Exposure to high androgens (male hormones) in the womb. That early hormone exposure can flip switches on certain genes related to metabolism, hormones, and reproductive health, setting the stage for things like insulin resistance and irregular periods later on.

So while you can’t change your genes, you can change how they’re expressed. That’s where lifestyle comes in.

Androgen Exposure in the Womb

One of the most well-studied pathways in PCOS starts before you’re even born. When a baby girl is exposed to too much androgen in the womb, it can impact how her ovaries and brain develop, setting the stage for hormone imbalances later in life.

That early exposure can flip certain genes, like P450c17, which controls enzymes involved in androgen production. When those enzymes go into overdrive, the body starts making more androgens than it should. This contributes to many of the classic PCOS symptoms, like irregular periods, acne, excess hair growth, and trouble with ovulation.

But those high androgen levels? They don’t always come directly from your mom. Sometimes these changes were set in motion generations ago and passed down. One study even showed that epigenetic changes can carry through at least three generations. So if your great-great-grandmother experienced high androgen exposure from things like chronic stress, poor nutrition, or environmental toxins, those changes may have been inherited by the women in your family, raising the chances of PCOS in later generations.

This is why PCOS often runs in families, but looks different from person to person. One woman might struggle most with insulin resistance and weight gain. Another might have irregular cycles or fertility challenges. Someone else might deal with acne or hair growth. How it shows up in your body depends on both your genetic wiring and everything your body has been exposed to throughout your life.

The bottom line? It’s not your fault, but there are things you can do to change the way your body responds now.

PCOS Can Be Passed Down for At Least Three Generations

While PCOS has strong genetic and epigenetic roots, the environment during pregnancy can tip the scale even further. A mom’s diet, stress levels, and especially her insulin levels during pregnancy all influence how her baby’s genes get expressed.

Here’s how it works: high insulin levels in pregnancy can trigger higher androgen production. And that extra androgen exposure in the womb can alter the baby’s hormonal development, raising the risk of PCOS later in life. This is one reason why maternal insulin resistance has been linked to a higher chance of PCOS in daughters.

Of course, no one chooses to have insulin resistance, but understanding how it affects pregnancy can be a game-changer. Because if we can break the cycle now, we can lower the risk for future generations.

You Did Not Cause Your PCOS

Understanding the role of epigenetics in PCOS is powerful because it removes the blame. You didn’t cause your PCOS. Your mom didn’t cause it either. Even if she has it too, it wasn’t passed down just through her diet or lifestyle. The groundwork for PCOS was likely laid generations ago.

And while we can’t change the past, we can change how we respond to it.

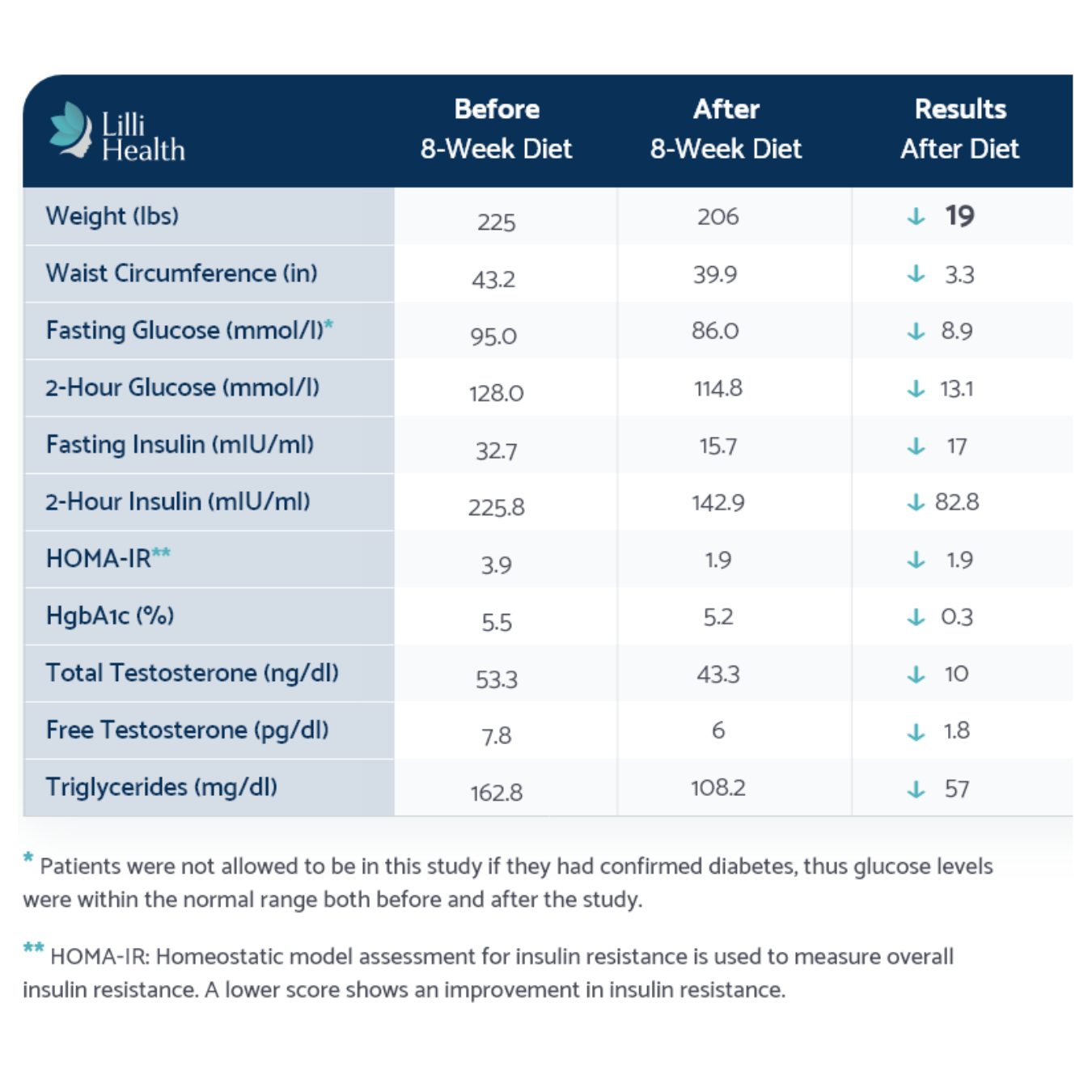

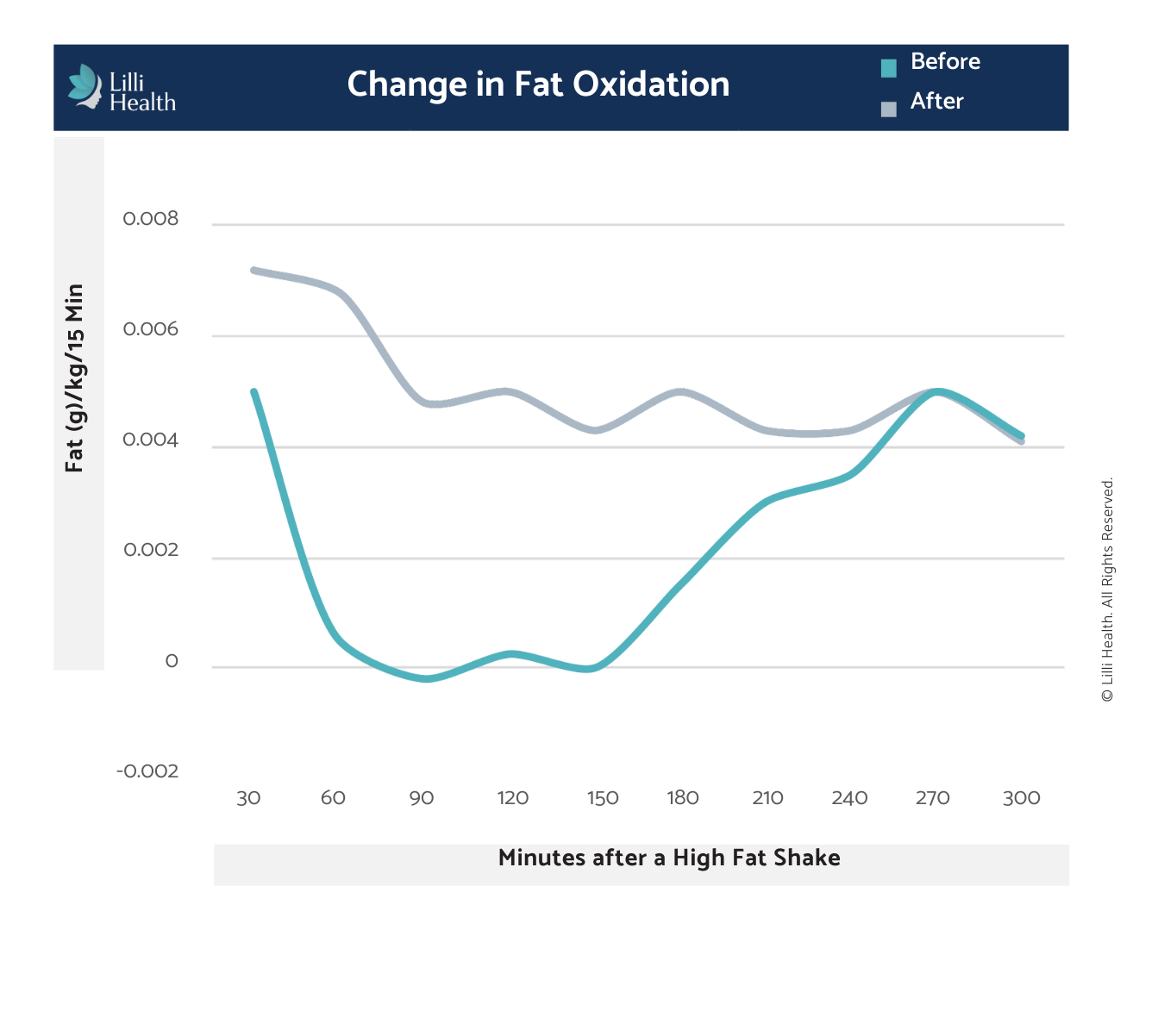

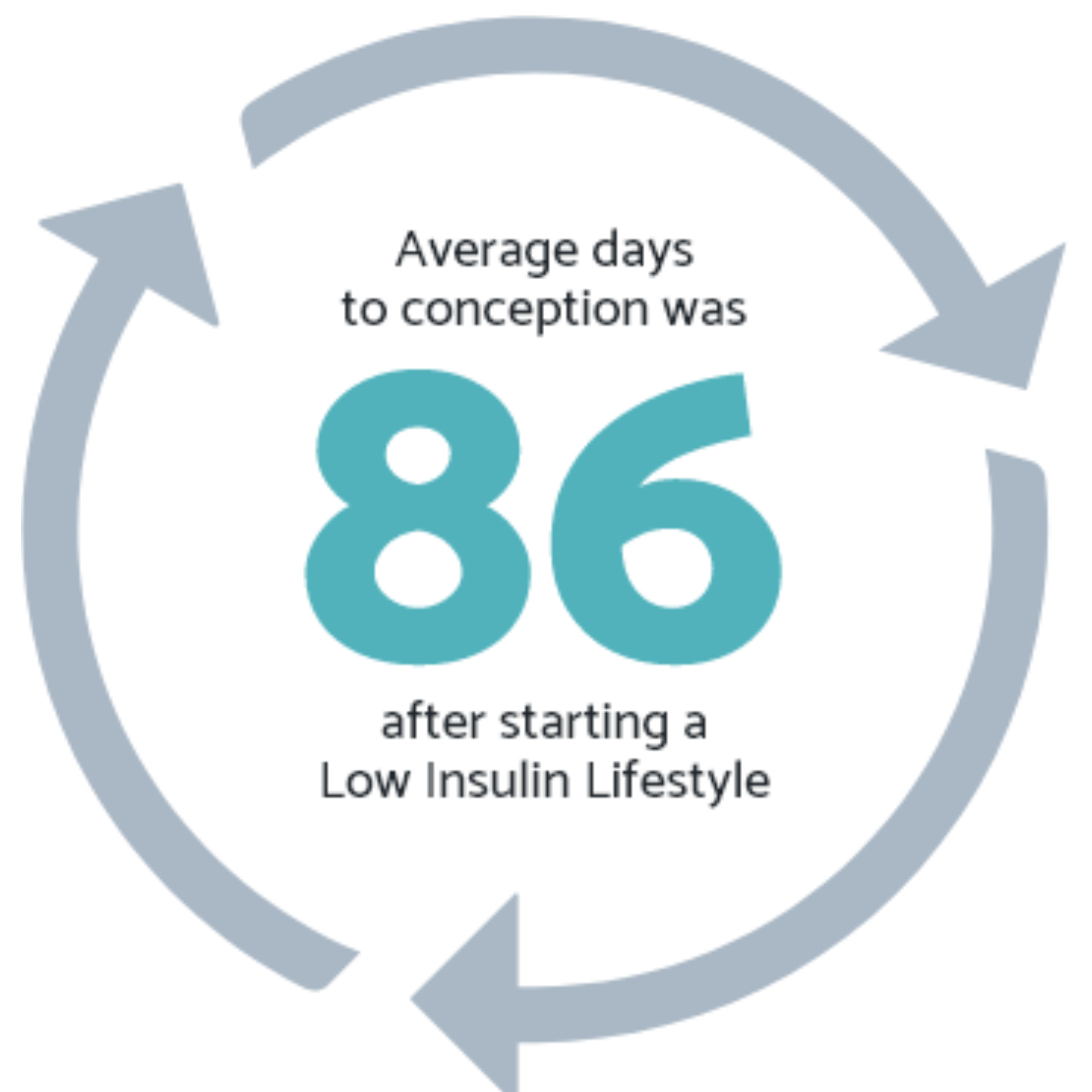

Research shows that targeting insulin resistance helps get to the root of PCOS. That’s why a Low Insulin Lifestyle can be so effective. By keeping insulin levels low, you help regulate androgen production, improve ovulation, and reduce the frustrating symptoms so many people with PCOS deal with—like acne, irregular cycles, weight struggles, and fatigue.

This isn’t about blame—it’s about empowerment. And knowing how to shift your body’s response starting right now.

The Takeaway

PCOS is not something you caused. It is not your fault. The roots of this condition run deep, spanning multiple generations. But the good news is that understanding the science behind PCOS gives you the power to manage it in a way that supports your body. While we cannot change the past, we can take control of our health moving forward.